Keeping sketchbooks is a valuable developmental tool for the artist as well as an evocative, fascinating record. I have yet to meet a serious or accomplished artist who does not have at least a small collection of drawing pads containing their sketches. These “image reservoirs”, bound or loose leaf, are an artist’s laboratory. In my case, such a private arena was invaluable for the practice of my skills of perceiving and creating images. To hone my rendering abilities I would draw from my imagination, my surroundings, my friends or choose subject matter from the works of other artists.

Yet, to use another analogy, sketchbooks have also served my imagination as a playground. In that private realm of line, shade, smudge and shape I can follow the contours of my fancy to soar beyond the constraints of the second dimension. Sometimes, my efforts come up short yet falter harmlessly against the non-condemning and confidential papyrus. Happily, I have only to begin anew with the turn of the page.

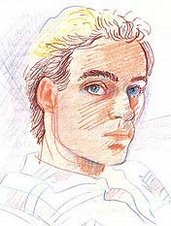

Over time, as I looked back through my early books, I noticed improvement, which inspired me to continue drawing. I endeavored, foremost, to learn the art of rendering the human form. Many of my earlier books were filled with pages of awkwardly posed, mannikin-like, pencil-drawn figures (often one to a page) in various attire, modern or ancient. I would begin with a skeleton sketch and build the basic musculature, then subsequently add skin and clothing. Sometimes I would place the figures on backgrounds such as a city street or in the context of some battle. However stilted and contrived these drawings, they were valuable exercises that eventually aided my observation of the human figure and my skill at drawing a natural-looking human form. Eventually the lines of the figures became more confident and flowing. The drawings began to possess more depth and volume. I also began to appreciate depicting the average, less-ideal human form.

Such a record of progress served as a consistent source of encouragement and a reminder of my development. In some cases, perusing my sketch books would renew my acquaintance of themes or techniques that I had toyed with but then abandoned. At such times, I would take up the rediscovered imagery and methods again with new vision —like engaging an old friend in conversation after a prolonged absence.

My medium of choice was originally a 2B lead pencil. This was convenient for erasing mistakes. As I experimented with softer leads, I discovered the useful shading technique of controlled smudging which allowed for smooth light-to- dark tones. Harder leads provided cleaner lines that gave my drawing a more finished look. Eschewing the use of lines and smudges all together, I briefly, in the early days, tried the pointillistic technique of shading with multitudinous dots created from the tip of a Flair brand marker. The effect was exciting to me as I was entering a phase marked by interest in gory subject matter. With the “dot” method of rendering, I could draw my monsters and melting figures with almost clinical precision. A form of this technique would serve me later as I drew pen-and-ink illustrations for printed publication.

In recent years, my favorite medium for drawing in my sketchbooks is black ball-point pen. Felt-tip markers tend to bleed through the paper over time and offer less of a range of line than that of a ball-point. The ball-point pen does not smudge like a pencil but it renders a surprising subtlety of shade. It reproduces well on a photo-copy machine and such pens are almost as cheap as their graphite and wood forebears.

My use of ball-point pen is significant. I no longer worry about erasing my mistakes. During the last half of my sketchbook-keeping career, I would most often fill the page with sketches. They seem to spin around each other and sometimes overlap, occupying the same space. Over the last few years, I have experimented with sketching with different colored pens as each color represents a particular image or plane of thought. A sketch in one particular color will be juxtaposed on top of another. The different colors allow me to more easily keep the images separate when I view them later. Originally, I developed this technique to save paper. Yet I became fascinated with it as a type of layering of realities. I feel this is analogous to objects in separate dimensions that are able to pass through one another without losing the integrity of their individual boundaries. More specifically, I liken it to the physical and spiritual realms as they interweave, overlap and interact.

My use of ball-point pen is significant. I no longer worry about erasing my mistakes. During the last half of my sketchbook-keeping career, I would most often fill the page with sketches. They seem to spin around each other and sometimes overlap, occupying the same space. Over the last few years, I have experimented with sketching with different colored pens as each color represents a particular image or plane of thought. A sketch in one particular color will be juxtaposed on top of another. The different colors allow me to more easily keep the images separate when I view them later. Originally, I developed this technique to save paper. Yet I became fascinated with it as a type of layering of realities. I feel this is analogous to objects in separate dimensions that are able to pass through one another without losing the integrity of their individual boundaries. More specifically, I liken it to the physical and spiritual realms as they interweave, overlap and interact.

Many of my later sketch books lean toward a “stream-of-consciousness” look —unlike my initial volumes which typically devoted one small drawing to a single expansive page. The difference could possibly reflect a more adult ability to entertain differing perspectives at once.

Layering colored sketches and not being concerned about mistakes serves my desire to record not just the final out-put of an idea, but the process by which I developed the idea. In the past, the initial stages of my drawings were erased or covered over. In using different colors in developing a sketch, I leave all levels of the drawing’s composition intact. I begin sketching loosely with a light blue pen. As my idea for the drawing becomes more focused, I then use a red pen to develop lines that are more final. Sometimes I complete the sequence with a black pen to delineate the final or near-final state of the drawing. If I plan to reproduce the layered drawing, I’ll make a more refined tracing of it. Meanwhile the entire process of the work is recorded in my sketch book.

This appreciation of the process involved in creating a drawing can apply to life. Are we not all “drawings” in progress? As I look back on my life as well as my art, I marvel at the twists and turns of the lines rendered in the events of my life and the changes in my outlook and personality. I am still in process of being “finished”. And I have an active role to play in my own development through the choices I make. As far as art is concerned, the record of my choices are partially recorded in my sketchbooks.

See an online version of one of my home-made pocket sketchbooks HERE !

BONUS: Check out this drawing tip!

Great primer on the practice of contour drawing. I had an instructor who encouraged us to imagine an ant is crawling along all of the lines and creases of the subject and your job is to follow it with your pen.https://t.co/l8J45yn0mO

Great primer on the practice of contour drawing. I had an instructor who encouraged us to imagine an ant is crawling along all of the lines and creases of the subject and your job is to follow it with your pen.https://t.co/l8J45yn0mO

— Jay Boucher (@HobokenPudding) July 27, 2020

(This chapter was originally part of a University essay paper from 1991)

No comments:

Post a Comment